Detailed Program Notes for “Currents”: Jonathan was killed in a battle against the Philistines

Published March 13, 2015 by Third Coast Percussion | Share this post!

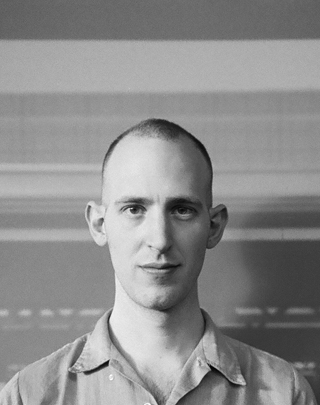

Sunday we will premiering not one but TWO commissions. Jonathan Pfeffer was one of the composers selected in our Emerging Composers Partnership Program and we’re looking forward to sharing his composition with you.

Sunday we will premiering not one but TWO commissions. Jonathan Pfeffer was one of the composers selected in our Emerging Composers Partnership Program and we’re looking forward to sharing his composition with you.

Jonathan was killed in battle against the Philistines is a one-act metatheatrical savage noise comedy for four percussionist-actors. Its form is appropriated from American psychiatrist Dr. George Vaillant’s four general classes of ego defense mechanisms: unconscious responses that regulate the perceived impact of sudden conflicts with conscience and culture. Jonathan employs Vaillant’s model, as well as references to Sufi poetry, the Tibetan Book of the Dead, the first Book of Samuel, post-Cagean composition, and verbatim slices of pop egomania to examine the futility and necessity of modern cultural production.

The percussionists embody caricatures that loosely represent each of the four levels of defense:

• Sean Connors as the pathological archetype, whose megalomania and delusional projections reshape external reality in order to maintain an inflated self-image at any cost. Not unlike an extreme case of bipolar disorder, he vacillates quickly between feelings of narcissism and persecution. This archetype freely exchanges characteristics with the immature archetype during the play.

• David Skidmore as the immature archetype, prone to paranoid and jealous outbursts in which he blames others for his own deficiencies. This archetype couches a self-serving agenda in half-informed pseudo-Marxist rhetoric. His scathing cultural analysis, while highly astute, more often than not comes across as self-righteous indignation. It could be argued that this attribute impedes his ability to negotiate a place in the modern world. Both immature and pathological archetypes tend to retreat into fantasy, engaging in delusions of grandeur of often Biblical proportions.

• Robert Dillon as the neurotic archetype, who also provides running commentary as the narrator/voice of “reason”. Suspicious of pleasure, he mistakenly equates satisfaction with suffering. As a result, he disassociates from intense sequences by concentrating on their purely intellectual components. While this archetype is associated with rationalization, this quality more frequently arises in the immature and pathological archetypes. At various points, this archetype appropriates the immature archetype’s incessant hypochondria.

• Peter Martin as the mature archetype, whose patience, gentle wit, and references to Eastern philosophy temper the heated exchanges between hot-headed pathological and immature archetypes. He is an exemplary model for how to cope with stress in a socially acceptable manner.

These thinly veiled, cartoonish exaggerations of the composer engage with one another in a series of intersecting monologues. The characters dissect the contemporary roles of both composer and percussionist within a culture increasingly detached from context. In a narrative device reminiscent of Joe Matt’s self-flagellating comics, the composer openly acknowledges and even incorporates his internal struggles into the libretto with a confrontational degree of intimacy.

Composed in a series of think-tank-style workshops with the ensemble, the music bears the mark of a true collaboration. The percussionists conjure a broken glass sound tapestry—gongs, cymbals, bowed brake drums, prepared crotales, amplified objects, and processed microphone feedback—which they execute concurrently with the dialogue. Alternately industrial and sensual, the division between acoustic and amplified timbres becomes illusory as pure sustained tones unravel into aleatoric melodies that re-emerge as pointillistic clusters. The soundscape ebbs and flows as a dynamic organism that directly responds to the descriptions of debilitating and often comical anxiety, like an abstract expressionist Peking Opera.

The result is an immersive and often disorienting sonic experience that owes as much to Richard Foreman as it does to Richard Pryor.